Uveitis updates from Retina Subspecialty Day 2017

NEW ORLEANS – Local treatment in uveitis has advanced in the past decade from simply depot injections with a short range of activity to more long-term treatments, said Thomas Albini, MD (Miami, Fla.).

Retisert 0.59 mg(fluocinolone acetonide, Bausch & Lomb; Bridgewater, N.J.) has been approved since 2005, but “comes with significant risks,” Dr. Albini said, including that 30-40% of patients who are implanted will need glaucoma surgery and almost everyone develops cataracts.

The 7-year results from the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) study concluded that after year 6, in the intent-to-treat group, those in the systemic arm did better than those in the implant; year 2 data seemed to favor those in the implant arm.

“But fewer than 20% after year 3 in the ITT arm received an implant, which means they were undertreated after year 4,” Dr. Albini said. “That could certainly explain the dropoff in VA and inflammation control.”

pSivida is woking on a phase 3 study with Iluvien (fluocinolone) and has “strong data,” he said.

Results of a phase 2 study on triamcinolone injected into the suprachoroidal space (CLS-TA, Clearside Biomedical, Alpharetta, GA) showed efficacy with “a minimal effect” on intraocular pressure (IOP) or cataract, Dr. Albini said.

Results from two integrated phase 3 studies on intravitreal sirolimus (Opsiria, Santen) met study endpoints and “seems to be very safe,” he said. Santen is expected to launch the drug as early as next spring, he added.

With Humira (adalimumab, AbbVie), ophthalmologists now have their first approved biologic for the treatment of uveitis; the drug met primary endpoints in two pivotal trials.

Mosquito-borne uveitis update

“All mosquito-borne uveitis” originated in either the tropics or in Africa and “followed the trade winds” around the world, said Emmett T. Cunningham, Jr, MD, PhD, MPH (Hillsborough, CA).

Globally, West Nile Virus is in the northern hemisphers, while Dengue, chikungunya, and Zika started tropically and then traveled.

Incubation can be up to 2 weeks, and 80% of people will be asymptomatic, he said. For those who do present with symptoms, they are likely to be fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise. Further, 5% of those with West Nile Virus will have encephalopathy, and are most likely to have ocular findings.

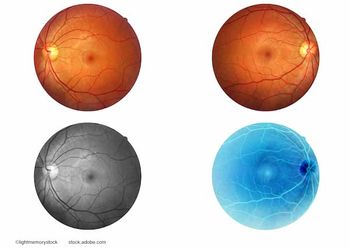

Dr. Cunningham noted multimodal imaging may be necessary, and should include wide-field color, fluorescein angiography, fundus autofluorescence to determine the location and pattern of the lesions.

“Prognosis will depend on two things: the number and site of the lesions,” he said.

Workup of patients with uveitis

First and foremost, “uveitis is not a disease. It is a description,” said James P. Dunn, Jr., MD (Philadelphia). While physicians “should always consider sarcoid and syphilis,” there is not one standard workup for uveitis.

The specific diagnosis is made using a careful history, physical exam, and then a more focused history that should be supplemented by the judicious use of lab tests, he said. Imaging studies may be supportive, but are not diagnostic.

The primary purpose of the workup should be to distinguish infectious from non-infectious, and to distinguish “purely ocular disease” from uveitis associated with systemic conditions.

“Intermediate uveitis with mild anterior chamber cells and macular edema is not panuveitis,” he said. “And cells do not necessarily mean flare.”

Other descriptors include ocular comorbidities, response to treatment, geography and travel, ethnicity, medical conditions, and family history. As an example, Dr. Dunn said if the patient is in Connecticut, a Lyme disease titer might be common, but “it’s not likely in Texas.”

What about idiopathic uveitis? “It’s everything except infectious uveitis,” he said. “It’s much better to use the term undifferentiated uveitis.”

-- Michelle Dalton, ELS

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.