Partial visual function restored in retinitis pigmentosa patient via gene therapy

In PIONEER study, investigators outline successes.

Reviewed by José-Alain Sahel, MD.

Gene therapy is taking its first steps in paving the way to vision restoration. In this case, a man with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) who had been blind for decades underwent an optogenetics treatment and he achieved partial restoration of vision, according to José-Alain Sahel, MD, chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology and director of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Eye Center.

“Optogenetics may enable mutation-independent, circuit-specific restoration of neuronal function in neurological diseases,” Sahel said.

Thus far, only one gene replacement treatment for early-onset RP caused by a mutation in the RPE65 gene has been developed. Optogenetic vision restoration, Sahel explained, is “a mutation-independent approach for restoring visual function” in patients with late-stage RP, at a point in the disease process when vision is lost. This treatment, a light-activating retinal gene therapy, is being evaluated in the ongoing phase 1/2a open-label PIONEER study to access the safety and efficacy of the therapy.

The patient received an intraocular injection of adeno-associated viral vector encoding ChrimsonR, provided by study sponsor GenSight Biologics, a channelrhodopsin, and light stimulation provided by goggles. The goggles, he explained, can detect local changes in light intensity and then project corresponding light pulses onto the retina with the goal of activating optogenetically transduced retinal ganglion cells. The investigators reported their results in Nature Medicine.1

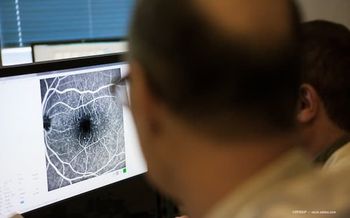

Results

The research team, which also included Botond Roska, MD, PhD, from the University of Basel, Switzerland, and the Institut de la Vision and StreetLab teams in Paris, reported their results in a 58-year-old man who had received a diagnosis RP 40 years previously and who had light perception vision. The patient’s eye with the worse vision was treated with 5.0 x 1010 vector genomes of the optogenetic vector. The patient was followed for 84 weeks and underwent ocular examinations, optical coherence tomography, color fundus photography, and fundus autofluorescence imaging during 15 visits. No safety issues arose during the study period.

About 4.5 months after the treatment, training with the goggles began after the ChrimsonR stabilized in the foveal ganglion cells. The patient began to report visual improvements while wearing the goggles 7 months after the start of training.

“The patient perceived, located, counted and touched different objects using the vector-treated eye alone while wearing the goggles,” the investigators wrote. “During visual perception, multichannel electroencephalographic recordings revealed object-related activity above the visual cortex.”

Moreover, the investigators noted that the patient could not visually detect any objects before injection with or without the goggles or after injection without the goggles.

“This is the first reported case of partial functional recovery in a neurodegenerative disease after optogenetic therapy,” they wrote.

The patient, who was the first to benefit from this treatment, was able to locate a large notebook, a small staple box, and tumblers. More patients were included in the study, but the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic interfered with their ability to undergo the examinations and testing.

Sahel also noted that investigators also examined whether the patient could recognize patterns while walking on the street.

“In the stimulated monocular condition but not in the natural binocular condition, the patient spontaneously reported identifying crosswalks and he could count the number of white stripes,” he said. “Subsequently, the patient testified to a major improvement in daily visual activities, such as detecting a plate, mug or phone, finding a piece of furniture in a room or detecting a door in a corridor but only when using the goggles. Thus, treatment by the combination of an optogenetic vector with light-stimulating goggles led to a level of visual recovery in this patient that was likely to be of meaningful benefit in daily life.”

The investigators currently are collecting safety and efficacy data and hope to be able to provide early reports in the coming months, Sahel said. A collaborator in the study is Botond Roska, MD, in Basel, and the Institut de la Vision and StreetLab teams in Paris. The study is sponsored by GenSight Biologics. Investigators are collecting clinical data on safety and efficacy and hope to be able to provide early reports in the coming months.

José-Alain Sahel, MD

E: sahelja@upmc.edu

This article is adapted from Sahel’s study, which was funded by the French Programme Investissements d’Avenir IHU FOReSIGHT, no. ANR-18-IAHU-01; RHU LIGHT4DEAF no. ANR-15-RHU-0001; BPI France (grant no. 2014-PRSP-15), Foundation Fighting Blindness, and Fédération des Aveugles de France and French National Research Agency (no. ANR-18-CHIN-0002). Sahel has personal financial interests in GenSight Biologics, Pixium Vision, SparingVision, Prophesee, Tilak, VegaVect, NewSight Reality, and Chronolife.

Reference

Sahel JA, Boulanger-Scemama E, Pagot C, et al. Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy. Nat Med.2021;27(7):1223-1229. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01351-4

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.