- Modern Retina Winter 2022

- Volume 2

- Issue 4

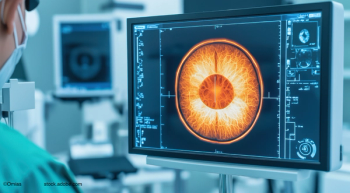

Significance of periphery in diabetic retinopathy diagnosis and management

Being able to visualize and evaluate the retinal periphery provides a better understanding of the disease status and supports a better treatment decision.

The standard of care for patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) has long been the dilated fundus exam, while the standard protocol in clinical studies has been fundus photography using the 7 standard fields established by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS-7SF). For decades, investigators have relied upon the ETDRS-7SF, which combines seven 30-degree images to create a 90-degree montage that encompasses the posterior pole almost completely. However, both the dilated fundus exam and the ETDRS-7SF have significant limitations.

Although dilated fundus exams can be valuable, they are also cumbersome for both clinician and patient. The accuracy and quality of ETDRS-7SF imagery varies based on patient cooperation, the presence of cataracts and other opacities, and the skill of the photographer. Perhaps most important, the ETDRS-7SF shows only 34% of the retina1 that is focused on the posterior pole, so it can only tell part of the story. Furthermore, the time required to review each image and/or montage then may be considered too long when compared with more modern modalities.

Pathology in the periphery

A substantial amount of pathology exists in the retinal periphery outside the reach of ETDRS-7SF. Research confirms DR pathology is present outside ETDRS-7SF photos in up to 40% of eyes.1 And studies have shown that 9% to 15% of eyes have peripheral pathology outside the ETDRS-7SF that indicates more severe disease based on the Diabetes Retinopathy Severity Scale (DRSS).1 Wessel et al found that some patients have widespread peripheral nonperfusion without significant pathology in the posterior pole,2 and 2 other studies demonstrated that approximately 10% of DR cases presented with lesions only outside the ETDRS-7SF area.2,3

Recently, results of the DRCR Retina Network’s Protocol AA study indicated that the presence of predominantly peripheral lesions and retinal nonperfusion on ultra-widefield (UWF) fluorescein angiography was associated with a significantly greater risk of ETDRS Diabetic Retinopathy Severity Scale worsening or a need for treatment over 4 years.4,5

The role of UWF

Considering the prevalence and significance of peripheral pathology in DR, visualizing and assessing the periphery is critical to providing the best possible care. For this reason, UWF imaging has become the standard

diagnostic and disease management tool at our clinic.

As defined by the International Widefield Imaging Study Group, UWF is an image centered on the fovea that includes retinal anatomy anterior to the vortex vein ampullae in all 4 quadrants.6 We use the Optos UWF imaging platform, which produces images encompassing more than 200° (82%) of the retina in a single capture.

The devices are easy to operate and improve efficiency compared with single-capture UWF imaging.7,8 Moreover, these advantages don’t require a sacrifice in quality; in fact, gradeability scores are excellent9 and a recent NHS-funded study found that UWF imaging was superior to ETDRS-7SF at identifying high-risk proliferative DR.10

UWF imaging has enhanced our confidence in managing DR patients. Because most of the periphery may be seen in 1 photo, more pathology is visible more quickly. I can detect and document primarily peripheral lesions (PPLs) as easily as when pathology is present in the posterior pole. I am better able to recognize neovascularization and nonperfusion, large areas of which may indicate an increased risk of progression (Figures 1 & 2).11

The focusing capacity of the Optos system, which is not technician-dependent, allows for both a consistent capture of the foveal avascular zone and easier identification of ischemic maculopathy.

In those of our rural clinics that don’t have UWF, I often feel uncomfortable assessing a patient based solely on a posterior pole angiogram and send them to one of our larger offices, where we can capture UWF and get a more comprehensive view of the retina.

The ability to see the perfusion status of the entire retina allows me to better assess the overall risk to the patient. I can also determine whether a patient is progressing, stable, or regressing almost instantly by comparing 200°, single-capture images rather than having to cycle through the 12 limited-field images of different parts of the retina captured with traditional fundus photography.

Conclusion

Although additional research is needed to gain a more complete understanding of the prevalence and significance of peripheral disease, there is no doubt that being able to visualize and evaluate the retinal periphery provides a better understanding of disease status and supports better treatment decisions. Dilated fundus examinations remain a critical part of DR management, but UWF imaging offers the opportunity to see and document as much of the retina as possible with greater efficiency and without sacrificing image quality. Consequently, clinicians can more confidently care for the growing number of diabetic patients and work to reduce their risk of vision loss.

Jose Agustin Martinez, MD, FASRS

e: jmartinez@austinretina.com

Martinez is a practicing vitreoretinal surgeon at Austin Retina Associates in Austin, Texas. He has no financial interests to disclose.

References

Aiello LP, Odia I, Glassman AR, et al. Comparison of early treatment diabetic retinopathy study standard 7-field imaging with ultrawide-field imaging for determining severity of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthlamol. 2019;137(1):65-73. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.4982

Wessel MM, Aaker GD, Parlitsis G, Cho M, D’Amico DJ, Kiss S. Ultra-wide-field angiography improves the detection and classification of diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2012;32(4):785-791. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182278b64

Bae K, Lee JY, Kim TH, et al. Anterior diabetic retinopathy studied by ultra-widefield angiography. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2016;30(5):344-351. doi:10.3341/kjo.2016.30.5.344

Marcus DM, Silva PS, Liu D, et al. Association of predominantly peripheral lesions on ultra-widefield imaging and the risk of diabetic retinopathy worsening over time. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(10):946-954. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.3131

Silva PS, Marcus DM, Liu D, et al. Association of ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography-identified retinal nonperfusion and the risk of diabetic retinopathy worsening over time. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140(10):936-945. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.3130

Choudhry, N. Classification & guidelines for wide field imaging: recommendations from the International Wide Field Imaging Study Group. Poster presented at: 51st Retina Society Annual Scientific Meeting; September 12-15, 2018; San Francisco, CA.

Lin CC, Li AS, Ma H, et al. Successful interventions to improve efficiency and reduce patient visit duration in a retina practice. Retina. 2021;41(10):2157-2162. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003169

Tornambe PE. The impact of ultra-widefield retinal imaging on practice efficiency. US Ophthalmic Review. 2017;10(1):27-30. https://www.optos.com/4a22d5/globalassets/www.optos.com/usor---practice-efficiency-with-uwf-tornambe.pdf

Silva PS, Horton MB, Clary D, et al. Identification of diabetic retinopathy and ungradable image rate with ultrawide field imaging in a national teleophthalmology program. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1360-1367. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.043

Maredza M, Mistry H, Lois N, Lois N, Aldington S, Waugh N; EMERALD Study Group. Surveillance of people with previously successfully treated diabetic macular oedema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy by trained ophthalmic graders: cost analysis from the EMERALD study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;103(11):1549-1554. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-318816.

Nicholson L, Ramu J, Chan EW, et al. Retinal nonperfusion characteristics on ultra-widefield angiography in eyes with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):626-631. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0440

Articles in this issue

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.