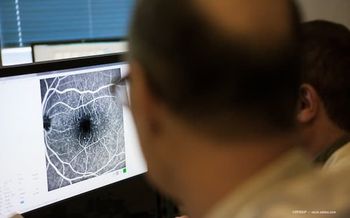

Study links cannabis use to lower risk of proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment repair

A recent study reveals cannabis use may lower the risk of proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment repair, suggesting potential therapeutic benefits.

A new study found that the use of cannabis might exert a moderately protective effect against the development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) after repair of retinal detachments (RDs),1 according to first author Ahmed M. Alshaikhsalama, MD, from the Department of Ophthalmology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

He was joined in this study, which was published in JAMA Ophthalmology, by investigators from the Department of Ophthalmology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Byers Eye Institute, Horngren Family Vitreoretinal Center, Department of Ophthalmology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA; and the Department of Ophthalmology, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Palo Alto.

The importance of this study is that PVR is the leading cause of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) repair failure, affecting up to 10% of cases.2-5Despite modern surgical advances in instrumentation and technique, PVR poses a major risk during the postoperative period,6 Alshaikhsalama and colleagues explained.

Some risk factors for PVR have been recognized, including increased age, cigarette smoking, globe trauma, vitreous hemorrhage at the time of repair, and myopia.2,7,8 Recognition of these is particularly helpful in preoperative counseling. However, little is known about any potential impact of cannabis.7,9,10

The investigators pointed out the Cannabis sativa plant and its primary active compound, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), have been used as a natural anti-inflammatory for centuries.11

Cannabis reduces microglial activity, expression of inflammatory cytokines, and retinal neurotoxicity through action on adenosine and cannabinoid receptors in animal models.12-14

However, cannabis also was found to be a potential risk factor for exacerbating thyroid eye disease, dry eye syndrome, and neuroretinal dysfunction.15,16

These contradictory effects led the investigators to evaluate the outcomes of patients who underwent primary RD repair and who used cannabis compared with matched control patients without a history of cannabis use.

Retrospective cohort study

The investigators examined data from electronic health records for a multicenter research network from February 1, 2005, to February 1, 2025. All participants had undergone an initial RD repair with pars plana vitrectomy with or without scleral buckle (SB), primary SB, or pneumatic retinopexy. The records were used to identify patients diagnosed with concomitant cannabis-related disorder together with confirmatory testing of cannabis in urine or blood compared with a control group without documented cannabis use, the authors recounted.

The main outcome measure was the relative risk (RR) of developing PVR and requiring subsequent complex RD repair at 6 months and 1 year of follow-up.

Each cohort had 1,193 matched patients. The mean ± standard deviation age was 53.2 (16.1) years; 1,662 were male (69.7%), 641 were female (26.9%), and the sex was unknown for 83 patients (3.5%).

“At 6 months, patients with concomitant cannabis use with RD repaired by any method had a reduced risk of developing subsequent PVR (25 events [2.10%] vs 52 events [4.36%]; RR, 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.30-0.77; P = 0.002) and requiring complex RD repair (37 [3.10%] vs 60 [5.03%]; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.41-0.92; P = 0.02) compared with controls. Similar results were observed at 1 year for both outcomes,” the investigators reported.

“This is the first study to examine a potential relationship between long-term cannabis use and subsequent PVR. While cannabis use demonstrated a lower RR for PVR, the small absolute reduction (~2%) may not be clinically meaningful. Confounders may account for all the observed associations. Future prospective studies are required to further clarify and characterize the effect of long-term cannabis use on PVR development and management,” Alshaikhsalama and colleagues advised.

References

Alshaikhsalama AM, Alsoudi AF, Mukhtar A, et al. Long-term cannabis use and risk of postoperative proliferative vitreoretinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025; published online July 3. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2025.1851

Girard P, Mimoun G, Karpouzas I, Montefiore G. Clinical risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment surgery. Retina. 1994;14:417-24. doi:

10.1097/00006982-199414050-00005 Ryan SJ. The pathophysiology of proliferative vitreoretinopathy in its management. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:188-193. doi:

10.1016/S0002-9394(14)75004-4 Charteris DG, Sethi CS, Lewis GP, Fisher SK. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: developments in adjunctive treatment and retinal pathology. Eye (Lond). 2002;16:369-374. doi:

10.1038/sj.eye.6700194 Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, Weiss C, Hilgers RD, Foerster MH; Scleral Buckling versus Primary Vitrectomy in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Study Group. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2142-2154. doi:

10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.013 Idrees S, Sridhar J, Kuriyan AE. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a review. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2019;59:221-240. doi:

10.1097/IIO.0000000000000258 Xiang J, Fan J, Wang J. Risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0292698. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0292698 PubMed Google Scholar Crossref Tseng W, Cortez RT, Ramirez G, Stinnett S, Jaffe GJ. Prevalence and risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy in eyes with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment but no previous vitreoretinal surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:1105-1115. doi:

10.1016/j.ajo.2004.02.008 Eliott D, Stryjewski TP, Andreoli MT, Andreoli CM. Smoking is a risk factor for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after traumatic retinal detachment. Retina. 2017;37:1229-1235. doi:

10.1097/IAE.0000000000001361 Wang MTM, Danesh-Meyer HV. Cannabinoids and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021;66:327-345. doi:

10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.07.002 Ryz NR, Remillard DJ, Russo EB. Cannabis roots: a traditional therapy with future potential for treating inflammation and pain. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2:210-216. doi:

10.1089/can.2017.0028 El-Remessy AB, Al-Shabrawey M, Khalifa Y, Tsai NT, Caldwell RB, Liou GI. Neuroprotective and blood-retinal barrier-preserving effects of cannabidiol in experimental diabetes. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(1):235-244. doi:

10.2353/ajpath.2006.050500 Liou GI, Auchampach JA, Hillard CJ, et al. Mediation of cannabidiol anti-inflammation in the retina by equilibrative nucleoside transporter and A2A adenosine receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(:5526-5531. doi:

10.1167/iovs.08-2196 El-Remessy AB, Khalil IE, Matragoon S, et al. Neuroprotective effect of (-)Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol in N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced retinal neurotoxicity: involvement of peroxynitrite. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(5):1997-2008. doi:

10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63558-4 PubMed Google Scholar Crossref Zong AM, Barmettler A. Effect of cannabis usage on thyroid eye disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025;41(2):179-185. doi:

10.1097/IOP.0000000000002770 Bondok M, Nguyen AX, Lando L, Wu AY. Adverse ocular impact and emerging therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids: a narrative review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:3529-3556. doi:

10.2147/OPTH.S501494

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.