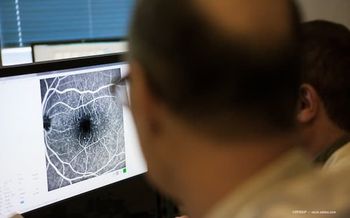

The Atrophy Advisor: An online tool to inform GA treatment decisions

Atrophy Advisor aids physicians in personalizing treatment for geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration, enhancing patient care and outcomes.

An online tool, Atrophy Advisor, was developed to guide physicians regarding treatments for patients with

Avery Kerwin, MD, the first author of the study, is from Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC. Elliot M. Perlman, MD, from the Rhode Island Eye Institute, Providence, and David J. Browning, MD, PhD, from Wake Forest University School of Medicine, were study coauthors.

The authors of this retrospective cohort study published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology,1 pointed out that numerous factors are involved in the onset and progression of GA. These include phenotypic risk factors such as the number of drusen and drusen area/volume;2,3 demographic factors such as age and smoking;3-5 and comorbidities, such as cataracts, hyperthyroidism, and chronic kidney disease.3

They also noted that faster GA progression is associated with increased baseline lesion area,6 the presence of more than one lesion,7 a shorter distance from a lesion to the fovea,7,8 and diffuse and banded autofluorescence patterns near GA borders.7,9-11 Genetic and molecular markers are also instrumental.3

“Collectively, the breadth of these risk factors underscores the heterogeneity of GA’s natural history and underscores the need to take an individualized approach during a patient’s risk assessment,” according to the authors.

Despite the introduction of treatments to slow GA progression that include injections and nutritional supplementation, the treatments are limited. The expansion of the GA lesion area has been studied12,13; however, the functional decline associated with involvement of the fovea is not reflected. Two studies14,15 suggested that the distance from the lesion to the fovea may be meaningful to the retinal function.

Focus of the current study

In the continuing investigation into GA progression, Dr. Kerwin and colleagues shifted their focus to the edge of the GA closest to the fovea. “This measure is more closely aligned with functional risk. We use this variable in conjunction with estimates of lifespan to attempt to more accurately predict which patients will benefit from complement inhibitor injections before permanent central vision loss occurs,” they explained.

Their study included 50 consecutive patients with GA secondary to nonexudative age-related macular degeneration. The investigators analyzed fundus images obtained at two or more timepoints to measure the distance between the fovea to the closest edge of a GA lesion. The demographic data, comorbidities, and corrected visual acuities were obtained from the patient records, and the lifespan estimates were calculated based on the University of Connecticut algorithm and estimates using the Atrophy Advisor and compared to observed outcomes.

The main outcomes were the GA edge-to-fovea distance, GA progression rate, corrected visual acuity, and predicted versus observed lifespan.

What did the analysis show?

The results showed that the median patient age was 78 years, and 64% of the patients were female.

The investigators reported that the baseline median GA-to-fovea distance was 792 µm (interquartile range [IQR]: 509-1213 µm), and the distance at the last follow-up examination decreased to 395 µm (IQR: 194-702 µm).

This showed that the median rate of GA progression was 122 µm/year (range, 2–627 µm/year), and there was a direct relationship between the initial distance and the progression rate (P = 0.006, R² = 0.146).

The calculation of the patient lifespan showed that the University of Connecticut and Atrophy Advisor estimated, respectively, 11.9 years (mean, 13.1 ±7.0 years; range, 3.4-41.2 years) and 11 years (mean, 8.1 years; range, 2.8-24.1 years), which affected the treatment guidance in 4% of cases, the investigators reported.

An important point is that the Atrophy Advisor includes two factors, i.e., the GA-to-fovea progression kinetics (foveal proximity of the nearest GA edge) and personalized estimates of lifespan incorporating demographic variables and comorbidities.

The authors concluded that “Atrophy Advisor is feasible for combining GA progression kinetics and lifespan estimates to inform treatment decisions. Variability in progression rates and lifespan predictions highlights the need for personalized approaches. Limitations include measurement variability and retrospective design; future studies should validate the tool in larger, prospective cohorts.”

References

Kerwin AF, Perlman EM, Browning DJ. Atrophy Advisor: a clinical tool for dry macular degeneration with geographic atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;S0002-9394(25)00636-1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2025.11.037. Epub ahead of print.

Schlanitz FG, Baumann B, Kundi M, et al. Drusen volume development over time and its relevance to the course of age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101:198-203. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308422

Heesterbeek TJ, Lorés-Motta L, Hoyng CB, Lechanteur YTE, den Hollander AI. Risk factors for progression of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020;40:140-170. doi:10.1111/opo.12675

Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, et al. Smoking and age related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(1):75-80. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.073643

Schmidt S, Hauser MA, Scott WK, et al. cigarette smoking strongly modifies the association of LOC387715 and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2006/05/01/ 2006;78:852-864. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/503822

Biarnés M, Arias L, Alonso J, et al. Increased fundus autofluorescence and progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: The GAIN Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:345-353.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.009

Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Sahel JA, Danis R, et al. Natural history of geographic atrophy progression secondary to age-related macular degeneration (Geographic Atrophy Progression Study). Ophthalmology. 2016;123:361-368. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.036

Keenan TD, Agrón E, Domalpally A, et al. Progression of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: AREDS2 Report Number 16. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(12):1913-1928. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.05.028

Batıoğlu F, Gedik Oğuz Y, Demirel S, Ozmert E. Geographic atrophy progression in eyes with age-related macular degeneration: role of fundus autofluorescence patterns, fellow eye and baseline atrophy area. Ophthalmic Res. 2014;52:53-9. doi:10.1159/000361077

Holz FG, Bindewald-Wittich A, Fleckenstein M, Dreyhaupt J, Scholl HP, Schmitz-Valckenberg S. Progression of geographic atrophy and impact of fundus autofluorescence patterns in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:463-72. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.041

Jeong YJ, Hong IH, Chung JK, Kim KL, Kim HK, Park SP. Predictors for the progression of geographic atrophy in patients with age-related macular degeneration: fundus autofluorescence study with modified fundus camera. Eye (Lond). 2014;28:209-18.doi:10.1038/eye.2013.275

Heier JS, Lad EM, Holz FG, et al. Pegcetacoplan for the treatment of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration (OAKS and DERBY): two multicentre, randomised, double-masked, sham-controlled, phase 3 trials. The Lancet. 2023;402(10411):1434-1448. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01520-9

Khanani AM, Patel SS, Staurenghi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of avacincaptad pegol in patients with geographic atrophy (GATHER2): 12-month results from a randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10411):1449-1458. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01583-0

Anegondi N, Steffen V, Sadda SR, et al. Visual loss in geographic atrophy: Learnings from the Lampalizumab Trials. Ophthalmology. 2025;132:420-430. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.11.017

Keenan TDL, Agrón E, Keane PA, Domalpally A, Chew EY. Oral antioxidant and lutein/zeaxanthin supplements slow geographic atrophy progression to the fovea in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2025;132:14-29. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.07.014

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.