- Modern Retina November and December 2025

- Volume 5

- Issue 4

Timely interventions can protect vision in patients with GA

Lock in patient adherence with discussion of study results.

A recent

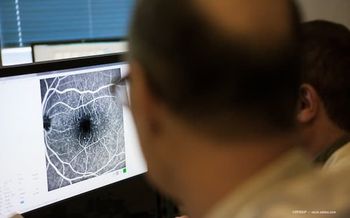

Because GA can wear many masks and present differently, Sambhara uses several imaging tools to identify and follow patients diagnosed with GA. The participants discussed the differences between treatments, which medications to use in different scenarios, dosing frequency, the safety profiles based on clinical trials, and real-world evidence regarding drug safety. The 2 approved medications for patients with GA are avacincaptad pegol intravitreal solution (Izervay; formerly Zimura; Astellas Pharma) and pegcetacoplan injection (Syfovre; Apellis Pharmaceuticals).

GA cases and considerations

Case 1.

A 79-year-old White woman, a practicing clinical psychologist, described worsening vision over the past year that did not improve with a new prescription. Her history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and osteoarthritis, and her ocular history included pseudophakia. Imaging showed slight GA, subsidence of the outer plexiform layer, a hypertransmission defect, and, on a near-infrared (NIR) image, well-delineated areas of nonsubfoveal atrophy.

“Different imaging modalities can do a good job at highlighting different aspects of GA,” Sambhara said. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed a well-delineated hypertransmission defect and an area of GA that corresponded with an area on the NIR image.

According to Sambhara, NIR and OCT do a better job of highlighting foveal involvement than fundus autofluorescence (FAF). “FAF does a good job identifying and delineating GA lesions well, but the combination of NIR imaging and OCT does a better job of highlighting foveal or nonfoveal involvement,” he said.

Treatment started with pegcetacoplan. Sambhara reviewed the images, noting that he orders them twice annually, 4 to 18 months in advance. The OCT and the FAF images were similar, and the patient’s vision was stable, he said.

This patient was committed to treatment, but others with the same scenario may not be, and the treatment discussions need to be more nuanced about GA. With such patients, Sambhara said he leans into imaging to promote adherence, motivation, and closer observation.

“Show them the pictures—what’s normal and not normal, even if they are not symptomatic,” he advised.

Case 2.

An 82-year-old White woman had GA in her only-seeing right eye, in which the vision was good but decreasing; the left eye had hand motions vision. Both eyes were glaucomatous.

An NIR image associated with its OCT showed nonsubfoveal multifocal GA lesions, with a high risk of rapid growth, and a small epiretinal membrane (ERM). FAF imaging showed perilesional hyperautofluorescence lesions, also characterized by rapid growth.

Most participants favored every-other-month treatment, based on results from the phase 3 OAKS (NCT03525613) and DERBY trials (NCT03525600), GALE extension study (NCT04770545), and GATHER studies. This treatment regimen creates a culture of adherence.

The participants opted for avacincaptad pegol because of its safety profile in this monocular patient, which was also Sambhara’s choice. The clinical picture remained stable for up to 8 months, after which consolidation of the peripapillary lesions was observed, accompanied by shrinkage of the unaffected areas. The central fovea remained unaffected.

Case 3.

An 87-year-old pseudophakic White man with worsening left-eye vision reported visual distortion and difficulty reading; he had undergone vitrectomy and ERM peeling in that eye with an area of GA. His vision was stable initially, but then the patient reported a change.

Pegcetacoplan was started. Following injection 3, some intraretinal fluid, a small choroidal neovascular membrane, and a small satellite lesion were seen inferior to the foveal center apart from the GA. The treatment discussion showed mixed preferences. Sambhara ultimately chose to treat the patient’s age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with anti-VEGF injections (faricimab-svoa; Vabysmo; Genentech) until he saw reduced fluid, which was when he restarted GA treatment. The patient did not receive both injections on the same day, a decision motivated by insurance payments and safety considerations in case an adverse event occurred.

The important point, Sambhara said, is that with conversion to exudative AMD, a detailed discussion with the patient can help maintain their commitment to more frequent dosing of the 2 diseases by increasing their knowledge of the disease processes.

Key takeaways

Early intervention can be impactful, as in case 1. “Treat the patient, not the picture, and lean into imaging to help guide treatment, management, and follow-up,” Sambhara commented.

In case 2, the monocular patient with nonsubfoveal atrophy, the discussion key points were the safety of GA treatments and risk factors for both fast-growing lesions and lesions that are more likely to progress quicker than slow-growing lesions.

In case 3, the key take-home points were how to best treat a patient with conversion to exudative AMD and that both diseases can be treated simultaneously on the same day. However, there are reasons to consider separating the anti-VEGF and complement inhibitor treatments in the same eye for a patient who might have both GA and exudative AMD, he concluded.

Articles in this issue

about 1 month ago

Inside the mindset of an early adopterabout 1 month ago

Challenges for young physicians treating patients with GAabout 1 month ago

A medical fellow finds some magic at the AAO Annual Meetingabout 1 month ago

AAO highlight: Looking ahead to 2026about 2 months ago

Understanding fluid fluctuation in retinal disordersabout 2 months ago

From AI to injury patterns: Insights from emerging ophthalmic researchNewsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.