Study highlights retinal vulnerability in patients with bipolar and depressive disorders

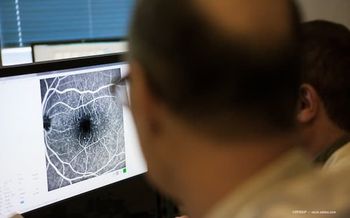

Retinal vascular change or degeneration already has been associated with Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, and the findings suggest that neurologic diseases impact ocular health.

Ophthalmologists are in the unique position of being able to help patients with diseases that are other than ocular in nature.

A new study, led by Jeffrey Chu, MD, from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, found that patients with a psychiatric disorder who also have a retinal disease may be at risk for increased visual loss compared to patients with a retinal disease alone. The investigators published their study in Eye.1

They explained that the relationship between cerebral and ocular disease was found to be of significant clinical utility. “Because the brain and the retina both develop from the neuroectoderm, they share many similar morphological and physiological properties. Therefore, changes within the retina may reflect pathological changes in the brain that are associated with cerebral disease. This allows the eyes to serve as a ‘window’ to evaluate disorders originating from the brain.”2

Retinal vascular change or degeneration already has been associated with Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, and the findings suggest that neurologic diseases impact ocular health.3,4

Psychiatric disorders have also been linked to ocular changes, specifically in the retina. Imaging of patients with schizophrenia has visualized retinal thinning and decreased macular thickness and volume.5-8 Those with bipolar disorder have significant global thinning of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) and lower ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL) volume.9-11 One study found that patients with major depressive disorder had significantly reduced GCL, IPL, and global and temporal superior RNFL thicknesses,12 all of which elucidate the effect of psychiatric disorders on the retinal structure. However, the authors pointed out, the manner by which these structural abnormalities lead to functional abnormalities and retinal disease and subsequent visual impairment has not been thoroughly investigated.

Determining the link between psychiatric and retinal disease

Chu and colleagues conducted an exploratory retrospective cohort study using data from a federated health research network containing over 95 million individuals across 50 healthcare organizations. Patients aged 50 to 89 years with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, retinal disease, and visual impairment defined by vision loss or blindness were identified. Patients eligible for entry into the study had a diagnosis of a particular psychiatric disorder of interest (case cohort), and the controls (control cohort) did not. Individuals in both cohorts were propensity score matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemias.

The stated study goal was to examine the risk of retinal disease in individuals with psychiatric disorders, ie, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The investigators also explored how a psychiatric disorder affects the risk of visual impairment in individuals with a retinal disease.

Link identified

After matching, the schizophrenia cohort was comprised of 160,414 matched individuals (average age, 65 years), 391,440 in the bipolar disorder cohort (average age, 64 years), and 1,962,380 in the major depressive disorder cohort (average age, 67 years).

“A recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with a decreased likelihood of having a retinal disease diagnosis, while recorded diagnoses of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were associated with an increased likelihood of diagnosis of a retinal disease. Across all psychiatric disorders, individuals with a retinal disease diagnosis had an increased risk of visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone,” Dr. Chu and colleagues reported.

They concluded, “This exploratory retrospective cohort study highlights that while individuals with recorded diagnoses of schizophrenia were less likely to have recorded diagnoses of a retinal disease, individuals with recorded diagnoses of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were more likely to have a retinal disease. However, across all psychiatric disorders, individuals with a concurrent retinal disease were more likely to have visual impairment compared to individuals with a retinal disease alone. Ultimately, these findings suggest closer ophthalmology monitoring may be warranted for patients with psychiatric conditions.”

References

Chu J, Shaia JK, Jeong H, et al. Risk of retinal disease and visual impairment in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Eye. 2025; published online May 20.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03851-w London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M. The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:44–53.

https://doi.org/10.1038/NRNEUROL.2012.227 .Choi S, Jahng WJ, Park SM, Jee D. Association of age-related macular degeneration on Alzheimer or Parkinson disease: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;210:41–47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJO.2019.11.001 .Shariflou S, Georgevsky D, Mansour H, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of retinal biomarkers in early on-set Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14:1000–1007.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205014666170329114445 .Lee WW, Tajunisah I, Sharmilla K, Peyman M, Subrayan V. Retinal nerve fiber layer structure abnormalities in schizophrenia and its relationship to disease state: evidence from optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7785–7792.

https://doi.org/10.1167/IOVS.13-12534 .Celik M, Kalenderoglu A, Sevgi Karadag A, Bekir Egilmez O, Han-Almis B, Şimşek A. Decreases in ganglion cell layer and inner plexiform layer volumes correlate better with disease severity in schizophrenia patients than retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: Findings from spectral optic coherence tomography. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;32:9–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURPSY.2015.10.006 .Cabezon L, Ascaso F, Ramiro P, et al. Optical coherence tomography: a window into the brain of schizophrenic patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90.

https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1755-3768.2012.T123.X .Samani NN, Proudlock FA, Siram V, et al. Retinal layer abnormalities as biomarkers of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:876–85.

https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/SBX130 .Mehraban A, Samimi SM, Entezari M, Seifi MH, Nazari M, Yaseri M. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in bipolar disorder. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:365–371.

https://doi.org/10.1007/S00417-015-2981-7 .Garcia-Martin E, Gavin A, Garcia-Campayo J, et al. Visual function and retinal changes in patients with bipolar disorder. Retina. 2019;39:2012–2021.

https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002252 .Kalenderoglu A, Sevgi-Karadag A, Celik M, Egilmez OB, Han-Almis B, Ozen ME. Can the retinal ganglion cell layer (GCL) volume be a new marker to detect neurodegeneration in bipolar disorder? Compr Psychiatry. 2016;67:66–72.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPPSYCH.2016.02.005 .Kalenderoglu A, Çelik M, Sevgi-Karadag A, Egilmez OB. Optic coherence tomography shows inflammation and degeneration in major depressive disorder patients correlated with disease severity. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:159–165.

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2016.06.039 .

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.